.

Isaiah 61:1-4, 8-11

John 1:6-8, 19-28

December 4, 2014

Advent 3 Joy

Year B

The prophet in the Isaiah reading has a wonderful task; he has come to announce to the Hebrew people the completion of their hopes and the hopes of their parents before them. Isaiah’s proclamation of good news and healing is a call to jubilation. It is being delivered to people who had been conquered by another nation, exiled, and they had verged on despair. These people have been oppressed for a long time and now they are returning home.

The people return home to Jerusalem, a city in ruins, and there they have a sense of hope, and new beginnings. They rejoice, though what they celebrate has not yet fully come to be. Their rejoicing, therefore, is a daring act. It is a high calling to celebrate in the face of trouble, persecution, or loss, and with opposition from others.

Going home is both symbolic and literal. Most of us come home literally, but even as we come home their remains deep inside of us a longing to come home in some other way. And that is the question I want to ask - what does it mean to come home in this way? What is that longing?

When is it that we are really “home?”

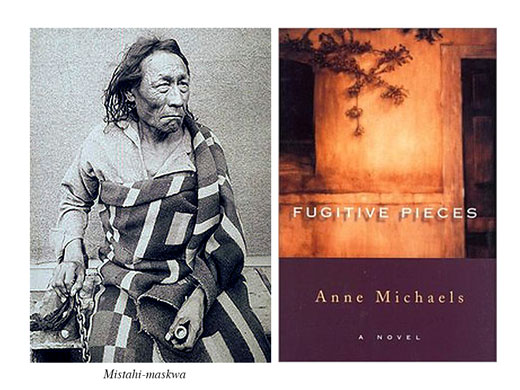

I am reading “Big Bear” by Hugh A. Dempsey. Big Bear, (Mistahi-maskwa) a plains Cree Indian was born in 1825 at Jackfish Lake close to North Battleford, Saskatchewan; he died on the Poundmaker Indian reservation in 1888. First and foremost Big Bear was a peacemaker and he spent most of his life attempting to convince the Queen’s government that the prairies were home to the Cree Plains Indians. Of course the government didn’t listen to Big Bear’s ideas but he never gave up - he spent his entire life working for justice, he worked in vain to keep the prairies for his people.

He lived in Montana for part of his life and when he returned to Canada for the last time he eventually signed a treaty in the middle of winter when his people were near starvation. That day he gave up his home on the prairie. He never again lived in freedom on the land he loved and cared for. His hopes and dreams would never be fulfilled, he had returned to a Jerusalem in ruins, a devastation that would not be reclaimed.

He continued to long for the old way of life, and he knew in his heart he couldn’t have that back. But it didn’t stop his longing. And there was no healing because the white man’s government would not listen to him. They wouldn’t allow him to live the way he wished to live. Big Bear’s people still, today, live in exile - the promise from the Old Testament is not complete for the Plains Cree - the garland instead of ashes and the oil of gladness instead of mourning is not fulfilled.

Big Bear’s story makes me wonder: Is Justice connected to being at home?

Does our longing grow out of a sense of an incomplete world? Will we only be coming home when justice and peace prevail? Can we only be at home both literally and emotionally when the rest of the world is at home too?

In the book Fugitive Pieces by Anne Michaels, she pursues similar ideas. In the story a young boy, Jakob Beer, is rescued from the mud of a buried Polish city during the Second World War and he is taken to an island in Greece by an unlikely saviour, the scientist and humanist, Athos Roussos. There, in the seclusion and tenderness of Athos’ house, they spend the last years of the Occupation in a precarious refuge made lavish with poetry and cartography, botany and art.

Jakob was about ten years old when his parents hid him in a secret childhood hiding place and he saw his parents murdered but he never saw or heard his sister Belle’s death and he spends his entire life longing to be reunited with her. Anne Michael’s tells a story of loss, the loss of place, of home, of family, the loss of one’s identity - and she describes the necessity of understanding our loss and emotional pain and the healing power of memory. She composes an ode to memory, to the poetry that lives within Jakob and this writing liberates him as it helps him recover his past.

A past that is filled with war, sorrow and pain. The writer says that, Jacob wasn‘t alone in Toronto in those years following the war “For most people living in Toronto then…their life was cut in half, they had to rediscover what home was - they had to begin again.” Questions about home and place are raised by this observation.

Jakob eventually transcends the tragedies of his youth; but his spirit remains forever linked with that of his lost sister. Belle haunts him because he doesn’t know what happened to her, there is no closure. He can only imagine and that imagining becomes a kind of devotion or honouring of her memory. He finally learns how to let go of Belle, and at the same time he finds a place in which to keep on loving her.

Fugitive Pieces says a lot about the condition of being an immigrant. Jacob never feels at home anywhere, not even in Greece. Michaels implies that integration to a new place for many immigrants is not possible.

Anne Michaels, in her story, asks us to think about home or place in a number of ways: She raises the question of finding a home in a foreign land, and of finding a place for the dead. If we are to live in peace with the part of ourselves that longs for wholeness, then the dead whom we love have to have a place. She also raises the question of the purpose of life, and she says that life must have meaning in order for us to find that place to come home to - that place, that home where we love ourselves and others. That place where we create justice. That place where we create a place for the needs of the world.

How does the third Sunday of Advent fit with this theme? The story of the coming of the Messiah is told over and over in Isaiah because the Messiah was and is the one who did come to create justice in the world. The Messiah is the one who understands goodness and the one who, with us, creates all that is good. (Embodiment theology)

Big Bear wanted those same things; he could have been, symbolically, the Messiah of his day. (For those of us who are Christian, that is! I wonder how excited he would be at that prospect.) Yesterday, in Winnipeg, the First Nations people elected Chief Perry Bellegarde from Saskatchewan to lead the Assembly of First Nations. It is a tough position to take on. Can Big Bear’s dream for his people ever be fulfilled? Can we find ways to work together to bring fairness and harmony to our country, and to all who live here?

In this Advent season we long for the story to be told because it is the story that we will create once again. It is Isaiah’s vision of justice and peace and love. The story leads us home - the story offers a way for us to create goodness in the world and in our communities. It is our opportunity to bring Jerusalem up out of the ashes, it is time to offer a garland instead of ashes a time to welcome strangers and foreigners into our midst. The story is about freedom. Big Bear never found freedom - at the end of his life - he was a victim of a corrupt system. He never returned home. He died on the Poundmaker reservation at the end of a three day blizzard on a morning when it was -30.

Jakob Beer found some freedom, he found the way home through poetry but his past was always with him. I suspect that some people never find the way home. Sometimes there are too many obstacles to overcome, sometimes it is just too complicated and sometimes it is impossible. Sometimes there is no space for jubilation or for celebration.

But others can and do find their way home. We can do our part to create justice, freedom, hope, and love in the world. I suspect that finding our way home covers a lot of ground. In the beginning we have to know ourselves, and understand just what our literal home is, and what it is we need to be happy. Once we have that then we can begin to understand the longing - the longing that nags at us and begs us to go forth in the world.

In her book Michaels is talking about finding peace and about creating a place for ourselves in the world that works for us, It is also about seeking forgiveness. It’s about the longing of the heart as we seek to find ways for others to forgive us, including the people we have wronged and the people we have neglected. She writes, “Of course it’s every peasant whose forgiveness must be sought. And must be sought, if possible, before they or we die. For when we die there is only silence.” This story is an invitation to review our lives and an opportunity to seek what we need to feel as though we are truly home.

We can ask: How will we seek wholeness, and forgiveness?

How will we settle the longing in our hearts for home?

How do we seek forgiveness from Big Bear and his people?

How do we seek forgiveness from the homeless, from the hungry?

How do we create justice in our communities?

How will we find our way home?

Sharon Ferguson-Hood

John 1:6-8, 19-28

December 4, 2014

Advent 3 Joy

Year B

The prophet in the Isaiah reading has a wonderful task; he has come to announce to the Hebrew people the completion of their hopes and the hopes of their parents before them. Isaiah’s proclamation of good news and healing is a call to jubilation. It is being delivered to people who had been conquered by another nation, exiled, and they had verged on despair. These people have been oppressed for a long time and now they are returning home.

The people return home to Jerusalem, a city in ruins, and there they have a sense of hope, and new beginnings. They rejoice, though what they celebrate has not yet fully come to be. Their rejoicing, therefore, is a daring act. It is a high calling to celebrate in the face of trouble, persecution, or loss, and with opposition from others.

Going home is both symbolic and literal. Most of us come home literally, but even as we come home their remains deep inside of us a longing to come home in some other way. And that is the question I want to ask - what does it mean to come home in this way? What is that longing?

When is it that we are really “home?”

I am reading “Big Bear” by Hugh A. Dempsey. Big Bear, (Mistahi-maskwa) a plains Cree Indian was born in 1825 at Jackfish Lake close to North Battleford, Saskatchewan; he died on the Poundmaker Indian reservation in 1888. First and foremost Big Bear was a peacemaker and he spent most of his life attempting to convince the Queen’s government that the prairies were home to the Cree Plains Indians. Of course the government didn’t listen to Big Bear’s ideas but he never gave up - he spent his entire life working for justice, he worked in vain to keep the prairies for his people.

He lived in Montana for part of his life and when he returned to Canada for the last time he eventually signed a treaty in the middle of winter when his people were near starvation. That day he gave up his home on the prairie. He never again lived in freedom on the land he loved and cared for. His hopes and dreams would never be fulfilled, he had returned to a Jerusalem in ruins, a devastation that would not be reclaimed.

He continued to long for the old way of life, and he knew in his heart he couldn’t have that back. But it didn’t stop his longing. And there was no healing because the white man’s government would not listen to him. They wouldn’t allow him to live the way he wished to live. Big Bear’s people still, today, live in exile - the promise from the Old Testament is not complete for the Plains Cree - the garland instead of ashes and the oil of gladness instead of mourning is not fulfilled.

Big Bear’s story makes me wonder: Is Justice connected to being at home?

Does our longing grow out of a sense of an incomplete world? Will we only be coming home when justice and peace prevail? Can we only be at home both literally and emotionally when the rest of the world is at home too?

In the book Fugitive Pieces by Anne Michaels, she pursues similar ideas. In the story a young boy, Jakob Beer, is rescued from the mud of a buried Polish city during the Second World War and he is taken to an island in Greece by an unlikely saviour, the scientist and humanist, Athos Roussos. There, in the seclusion and tenderness of Athos’ house, they spend the last years of the Occupation in a precarious refuge made lavish with poetry and cartography, botany and art.

Jakob was about ten years old when his parents hid him in a secret childhood hiding place and he saw his parents murdered but he never saw or heard his sister Belle’s death and he spends his entire life longing to be reunited with her. Anne Michael’s tells a story of loss, the loss of place, of home, of family, the loss of one’s identity - and she describes the necessity of understanding our loss and emotional pain and the healing power of memory. She composes an ode to memory, to the poetry that lives within Jakob and this writing liberates him as it helps him recover his past.

A past that is filled with war, sorrow and pain. The writer says that, Jacob wasn‘t alone in Toronto in those years following the war “For most people living in Toronto then…their life was cut in half, they had to rediscover what home was - they had to begin again.” Questions about home and place are raised by this observation.

Jakob eventually transcends the tragedies of his youth; but his spirit remains forever linked with that of his lost sister. Belle haunts him because he doesn’t know what happened to her, there is no closure. He can only imagine and that imagining becomes a kind of devotion or honouring of her memory. He finally learns how to let go of Belle, and at the same time he finds a place in which to keep on loving her.

Fugitive Pieces says a lot about the condition of being an immigrant. Jacob never feels at home anywhere, not even in Greece. Michaels implies that integration to a new place for many immigrants is not possible.

Anne Michaels, in her story, asks us to think about home or place in a number of ways: She raises the question of finding a home in a foreign land, and of finding a place for the dead. If we are to live in peace with the part of ourselves that longs for wholeness, then the dead whom we love have to have a place. She also raises the question of the purpose of life, and she says that life must have meaning in order for us to find that place to come home to - that place, that home where we love ourselves and others. That place where we create justice. That place where we create a place for the needs of the world.

How does the third Sunday of Advent fit with this theme? The story of the coming of the Messiah is told over and over in Isaiah because the Messiah was and is the one who did come to create justice in the world. The Messiah is the one who understands goodness and the one who, with us, creates all that is good. (Embodiment theology)

Big Bear wanted those same things; he could have been, symbolically, the Messiah of his day. (For those of us who are Christian, that is! I wonder how excited he would be at that prospect.) Yesterday, in Winnipeg, the First Nations people elected Chief Perry Bellegarde from Saskatchewan to lead the Assembly of First Nations. It is a tough position to take on. Can Big Bear’s dream for his people ever be fulfilled? Can we find ways to work together to bring fairness and harmony to our country, and to all who live here?

In this Advent season we long for the story to be told because it is the story that we will create once again. It is Isaiah’s vision of justice and peace and love. The story leads us home - the story offers a way for us to create goodness in the world and in our communities. It is our opportunity to bring Jerusalem up out of the ashes, it is time to offer a garland instead of ashes a time to welcome strangers and foreigners into our midst. The story is about freedom. Big Bear never found freedom - at the end of his life - he was a victim of a corrupt system. He never returned home. He died on the Poundmaker reservation at the end of a three day blizzard on a morning when it was -30.

Jakob Beer found some freedom, he found the way home through poetry but his past was always with him. I suspect that some people never find the way home. Sometimes there are too many obstacles to overcome, sometimes it is just too complicated and sometimes it is impossible. Sometimes there is no space for jubilation or for celebration.

But others can and do find their way home. We can do our part to create justice, freedom, hope, and love in the world. I suspect that finding our way home covers a lot of ground. In the beginning we have to know ourselves, and understand just what our literal home is, and what it is we need to be happy. Once we have that then we can begin to understand the longing - the longing that nags at us and begs us to go forth in the world.

In her book Michaels is talking about finding peace and about creating a place for ourselves in the world that works for us, It is also about seeking forgiveness. It’s about the longing of the heart as we seek to find ways for others to forgive us, including the people we have wronged and the people we have neglected. She writes, “Of course it’s every peasant whose forgiveness must be sought. And must be sought, if possible, before they or we die. For when we die there is only silence.” This story is an invitation to review our lives and an opportunity to seek what we need to feel as though we are truly home.

We can ask: How will we seek wholeness, and forgiveness?

How will we settle the longing in our hearts for home?

How do we seek forgiveness from Big Bear and his people?

How do we seek forgiveness from the homeless, from the hungry?

How do we create justice in our communities?

How will we find our way home?

Sharon Ferguson-Hood